Last Update:

IIFE for Complex Initialization

Table of Contents

What do you do when the code for a variable initialization is complicated? Do you move it to another method or write inside the current scope?

In this blog post, I’d like to present a trick that allows computing a value for a variable, even a const variable, with a compact notation.

Updated in Jan 2026: improved code, added C++26 section, added [&] section, updated code samples and added links to Compiler Explorer.

Intro

I hope you’re initializing most variables as const (so that the code is more explicit, and also compiler can reason better about the code and optimize).

For example, it’s easy to write:

const int myParam = inputParam * 10 + 5;

or even:

const int myParam = bCondition ? inputParam*2 : inputParam + 10;

But what about complex expressions? When we have to use several lines of code, or when the ? operator is not sufficient.

‘It’s easy’ you say: you can wrap that initialization into a separate function.

While that’s the right answer in most cases, I’ve noticed that in reality a lot of people write code in the current scope. That forces you to stop using const and code is a bit uglier.

You might see something like this:

int myVariable = 0; // this should be const...

if (bFirstCondition)

myVariable = bSecondCondition ? computeFunc(inputParam) : 0;

else

myVariable = inputParam * 2;

// more code of the current function...

// and we assume 'myVariable` is const now

The code above computes myVariable which should be const. But since we cannot initialize it in one line, then the const modifier is dropped.

I highly suggest wrapping such code into a separate method, but recently I’ve come across a new option.

I’ve got the idea from a great talk by Jason Turner about “Practical Performance Practices” where among various tips I’ve noticed “IIFE”.

The IIFE acronym stands for “Immediately-invoked function expression”. Thanks to lambda expression, it’s now available in C++. We can use it for complex initialization of variables.

Extra: You might also encounter: IILE, which stands for “Immediately Invoked Lambda Expression”.

How does it look like?

IIFE

The main idea behind IIFE is to write a small lambda that computes the value:

const auto var = [&...] {

return /* some complex code here */;

}(); // call it!

var is const even when you need several lines of code to initialize it!

The critical bit is to call the lambda at the end. Otherwise it’s just a definition.

The imaginary code from the previous section could be rewritten to:

const int myVariable = [&] {

if (bFirstCondition)

return bSecondCondition ? computeFunc(inputParam) : 0;

else

return inputParam * 2;

}(); // call!

// more code of the current function...

The above example shows that the original code was enclosed in a lambda.

We can also be more expressive and capture only needed things:

const int myVariable = [&inputParam] {

if (bFirstCondition)

return bSecondCondition ? computeFunc(inputParam) : 0;

else

return inputParam * 2;

}(); // call!

// more code of the current function...

The expression takes no parameters but captures the current scope by reference (or some explicit variables). Also, look at the last line of the declaration, () - we’re invoking the function immediately.

Additionally, since this lambda takes no parameters, we can skip () in the declaration. Only [] is required at the beginning, since it’s the lambda-introducer .

Improving Readability of IIFE

One of the main concerns behind IIFE is readability. Sometimes it’s not easy to see that () at the end.

How can we fix that?

Some people suggest declaring a lambda above the variable declaration and just calling it later:

auto initialiser = [&] {

return /* some complex code here */;

};

const auto var = initialiser(); // call it

The issue here is that you need to find a name for the initializer lambda, but I agree that’s easy to read.

And another technique involves std::invoke() that is expressive and shows that we’re calling something:

const auto var = std::invoke([&] {

return /* some complex code here */;

});

Note: std::invoke() is located in the <functional> header and it’s available since C++17.

In the above example, you can see that we clearly express our intention, so it might be easier to read such code.

Now back to you:

Which method do you prefer?

- just calling

()at the end of the anonymous lambda? - giving a name to the lambda and calling it later?

- using

std::invoke() - something else?

Should we capture the whole context with & ?

Short answer: capture only what you need.

Using [&] is concise and mirrors the “local scope” feel of the original code. But capture‑all by reference hides dependencies and makes it easy to accidentally use something that later becomes a dangling reference.

That’s why it’s best to write:

const auto value = [&inputParam, &anotherValue] {

// ...

return /* computed value */;

}();

[&] is convenient and safe for IIFE in most cases, but it’s also the least explicit. For code that will evolve or be reviewed often, prefer a precise capture list to make dependencies obvious and avoid surprises.

C++26 Updates

From the start of the article I wrote that you don’t need to write () to indicate the argument list… but until C++26 we had had to write:

const auto value = [inputParam]() noexcept {

if (/*condition*/)

return inputParam*2.0;

return inputParam;

}();

Do you see []() noexcept… ?

Up to C++26 there was a limitation:

Confusingly, the current Standard requires the empty parens when using the

mutable(an other) keyword. This rule is unintuitive, causes common syntax errors, and clutters our code.

This also applied to noexcept, attributes and other specifiers.

In summary, since C++26 you can omit the () if there are no parameters to declare/pass to the lambda.

Use Case of IIFE

Ok, the previous examples were all super simple, and maybe even convoluted… is there a better and more practical example?

How about building a simple HTML string?

Our task is to produce an HTML node for a link:

As input, you have two strings: link and text (might be empty).

The output: a new string:

<a href="link">text</a>

or

<a href="link">link</a> (when text is empty)

We can write a following function:

std::string BuildStringTest(std::string link, std::string text) {

std::string html;

html = "<a href=\"" + link + "\">";

if (!text.empty())

html += text;

else

html += link;

html += "</a>";

return html;

}

Alternatively we can also compact the code:

std::string BuildStringTest2(std::string link, std::string text) {

std::string html;

const auto& inText = text.empty() ? link : text;

html = "<a href=\"" + link + "\">" + inText + "</a>";

return html;

}

Ideally, we’d like to have html as const, so we can rewrite it as:

std::string BuildStringTestIIFE(std::string link, std::string text) {

const std::string html = [&link, &text] {

std::string out = "<a href=\"" + link + "\">";

if (!text.empty())

out += text;

else

out += link;

out += "</a>";

return out;

}(); // call ()!

return html;

}

Or with a more compact code:

std::string BuildStringTestIIFE2(std::string link, std::string text) {

const std::string html = [&link, &text] {

const auto& inText = text.empty() ? link : text;

return "<a href=\"" + link + "\">" + inText + "</a>";

}(); // call!

return html;

}

Here’s the code @Compiler Explorer

Do you think that’s acceptable?

Try rewriting the example below, maybe you can write nicer code?

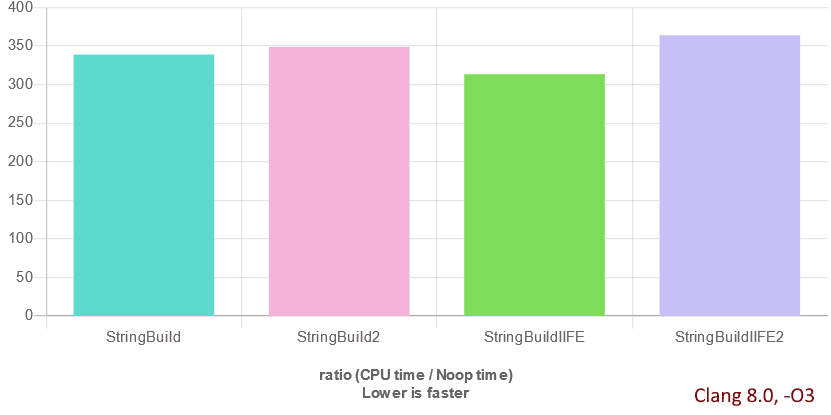

A Benchmark of IIFE

With IIFE, we not only get a clean way to initialize const variables, but since we have more const objects, we might get better performance.

Is that true? Or maybe longer code and creation of lambda makes things slower?

For the HTML example, I wrote a benchmark that tests all four version:

And it looks like we’re getting 10% with IIFE! (also similar result with recent compilers, as of 2026)

Some notes:

- This code shows the rough impact of the IIFE technique, but it was not written to get the super-fast performance. We’re manipulating string here so many factors can affect the final result.

- it seems that if you have less temporary variables, the code runs faster (so

StringBuildis slightly faster thanStringBuild2and similarly IIFE and IIFE2) - We can also use

string::reserveto preallocate memory, so that each new string addition won’t cause reallocation.

You can check other tests here: @QuickBench, and see the recent version @QuickBench Clang 17.0

It looks like the performance is not something you need to be concerned with. The code works sometimes faster, and in most of the cases the compiler should be able to generate similar code as the initial local version

Summary

Would you use such a thing in your code?

In C++ Coding Guideline we have a suggestion that it’s viable to use it for complex init code:

C++ Core Guidelines - ES.28: Use lambdas for complex initialization,

I am a bit sceptical to such expression, but I probably need to get used to it. I wouldn’t use it for a long code. It’s perhaps better to wrap some long code into a separate method and give it a proper name. But if the code is 2 or three lines long… maybe why not.

Also, if you use this technique, make sure it’s readable. Leveraging std::invoke() seems to be a great option.

I want to thank Mariusz Jaskółka from for the review, hints about compacting the code and also perf improvements with reserve().

Back to you

- What do you think about such syntax? Have you used it in your projects?

- Do you have any guidelines about such thing?

- Is such expression better than having lots of small functions?

References and Books

- Herb Sutter Blog: Complex initialization for a const variable

- C++ Weekly - Ep 32 - Lambdas For Free

- Complex Object Initialization Optimization with IIFE in C++11 - from Jason Turner’s Blog

- C++ IIFE in quick-bench.com

- C++ Core Guidelines - ES.28: Use lambdas for complex initialization,

Books:

I've prepared a valuable bonus for you!

Learn all major features of recent C++ Standards on my Reference Cards!

Check it out here: