Last Update:

C++20 Ranges: The Key Advantage - Algorithm Composition

Conceptually a Range is a simple concept: it’s just a pair of two iterators - to the beginning and to the end of a sequence (or a sentinel in some cases). Yet, such an abstraction can radically change the way you write algorithms. In this blog post, I’ll show you a key change that you get with C++20 Ranges.

By having this one layer of abstraction on iterators, we can express more ideas and have different computation models.

Updated in Mar 2023: added notes on C++23.

Computation models

Let’s look at a simple example in “regular” STL C++.

It starts from a list of numbers, selects even numbers, skips the first one and then prints them in the reverse order:

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

const std::vector numbers = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10};

auto even = [](int i) { return 0 == i % 2; };

std::vector<int> temp;

std::copy_if(begin(numbers), end(numbers), std::back_inserter(temp), even);

std::vector<int> temp2(begin(temp)+1, end(temp));

for (auto iter = rbegin(temp2); iter!=rend(temp2); ++iter)

std::cout << *iter << ' ';

}

Play @Compiler Explorer.

The code does the following steps:

- It creates

tempwith all even numbers fromnumbers, - Then, it skips one element and copies everything into

temp2, - And finally, it prints all the elements from

temp2in the reverse order.

(*): Instead of temp2 we could just stop the reverse iteration before the last element, but that would require to find that last element first, so let’s stick to the simpler version with a temporary container…

(*): The early version of this article contained a different example where it skipped the first two elements, but it was not the best one and I changed it (thanks to various comments).

I specifically used names temp and temp2 to indicate that the code must perform additional copies of the input sequence.

And now let’s rewrite it with Ranges:

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

#include <iostream>

#include <ranges> // new header!

int main() {

const std::vector numbers = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10};

auto even = [](int i) { return 0 == i % 2; };

using namespace std::views;

auto rv = reverse(drop(filter(numbers, even), 1));

for (auto& i : rv)

std::cout << i << ' ';

}

Play @Compiler Explorer.

Wow! That’s nice!

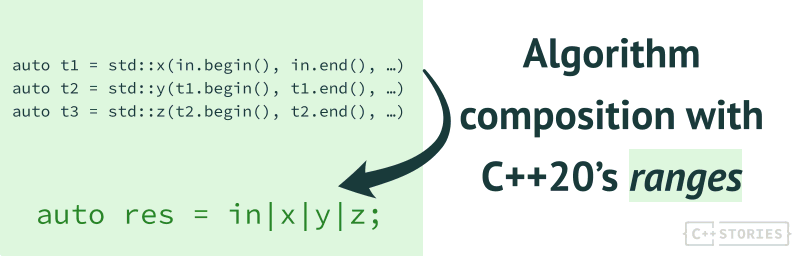

This time, we have a completely different model of computation: Rather than creating temporary objects and doing the algorithm step by step, we wrap the logic into a composed view.

Before we discuss code, I should bring two essential topics and loosely define them to get the basic intuition:

Range - Ranges are an abstraction that allows a C++ program to operate on elements of data structures uniformly. We can look at it as a generalization over the pair of two iterators. On minimum a range definesbegin()andend()to elements. There are several different types of ranges: containers, views, sized ranges, borrowed ranges, bidirectional ranges, forward ranges and more.

Container - It’s a range that owns the elements.

View - This is a range that doesn’t own the elements that thebegin/endpoints to. A view is cheap to create, copy and move.

Our code does the following (inside out):

- We start from

std::views::filterthat additionally takes a predicateeven, - Then, we add

std::views::drop(drop one element from the previous step), - And the last view is to apply a

std::reverseview on top of that, - The last step is to take that view and iterate through it in a loop.

Can you see the difference?

The view rv doesn’t do any job when creating it. We only compose the final receipt. The execution happens lazy only when we iterate through it.

Left String Trim & UpperCase

Let’s have a look at one more example with string trimming:

Here’s the standard version:

const std::string text { " Hello World" };

std::cout << std::quoted(text) << '\n';

auto firstNonSpace = std::find_if_not(text.begin(), text.end(), ::isspace);

std::string temp(firstNonSpace, text.end());

std::transform(temp.begin(), temp.end(), temp.begin(), ::toupper);

std::cout << std::quoted(temp) << '\n';

Play @Compiler Explorer.

And here’s the ranges version:

const std::string text { " Hello World" };

std::cout << std::quoted(text) << '\n';

auto conv = std::views::transform(

std::views::drop_while(text, ::isspace),

::toupper

);

std::string temp(conv.begin(), conv.end());

std::cout << std::quoted(temp) << '\n';

Play @Compiler Explorer.

This time we compose views::drop_while with views::transfrm. Later once the view is ready, we can iterate and build the final temp string.

This article started as a preview for Patrons, sometimes even months before the publication. If you want to get extra content, previews, free ebooks and access to our Discord server, join the C++ Stories Premium membership or see more information.

Ranges views and Range adaptor objects

The examples used views from the std::views namespace, which defines a set of predefined Range adaptor objects. Those objects and the pipe operator allow us to have even shorter syntax.

According to C++ Reference:

if C is a range adaptor object and R is a

viewable_range, these two expressions are equivalent:C(R)andR | C.

An adaptor usually creates a ranges::xyz_view object. For example we could rewrite our initial example into:

std::ranges::reverse_view rv{

std::ranges::drop_view {

std::ranges::filter_view{ numbers, even }, 1

}

};

The code works in the same way as our std::views::... approach… but potentially it’s a bit worse, see below:

std::views::xyz vs ranges::xyz_view ?

What should we use std::views::drop or explicit std::ranges::drop_view?

What’s the difference?

To understand the difference I’d like to point out to some fragment of a great article by Barry Revzin. Prefer views::meow @Barry’s C++ Blog

Barry compares:

auto a = v | views::transform(square);

auto b = views::transform(v, square);

auto c = ranges::transform_view(v, square);

He claims that views::transform (or views::meow in a more generic way) is a user-facing algorithm and should be preferred over option c (which should be considered implementation detail).

For example, views::as_const produces a view of const objects. For a view of int& it builds a view of const int& objects. But if you pass already const int& then this view returns the initial view. So views::meow is usually smarter and can make more choices than ranges::meow_view.

The only sensible use case for ranges::meow_view is when you implement another custom view. In that case, it’s best to “generate” the ranges::meow directly.

Always prefer

views::meowoverranges::meow_view, unless you have a very explicit reason that you specifically need to use the latter - which almost certainly means that you’re in the context of implementing a view, rather than using one.

C++23 (missing parts)

You might notice that I still need an additional step to build the final string out of a view. This is because Ranges are not complete in C++20, and we’ll get more handy stuff in C++23.

One of the most prominent and handy feature of C++23 Ranges is ranges::to. In short we’ll be able to write std::ranges::to<std::string>(); and thus the code will get even simpler:

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <ranges>

int main() {

const std::string text { " Hello World" };

std::cout << std::quoted(text) << '\n';

auto temp = text |

std::views::drop_while(isspace) |

std::views::transform(::toupper) |

std::ranges::to<std::string>();

std::cout << std::quoted(temp) << '\n';

}

You can try that in the latest version of MSVC (as of late March 2023): @Compiler Explorer

Now, temp is a string created from the view. The composition of algorithms and the creation of other containers will get even simpler.

Predefined views

Here’s the list of predefined views that we get with C++20:

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

views::all |

returns a view that includes all elements of its range argument. |

filter_view/filter |

returns a view of the elements of an underlying sequence that satisfy a predicate. |

transform_view/transform |

returns a view of an underlying sequence after applying a transformation function to each element. |

take_view/take |

returns a view of the first N elements from another view, or all the elements if the adapted view contains fewer than N. |

take_while_view/take_while |

Given a unary predicate pred and a view r, it produces a view of the range [begin(r), ranges::find_if_not(r, pred)). |

drop_view/drop |

returns a view excluding the first N elements from another view, or an empty range if the adapted view contains fewer than N elements. |

drop_while_view/drop_while |

Given a unary predicate pred and a view r, it produces a view of the range [ranges::find_if_not(r, pred), ranges::end(r)). |

join_view/join |

It flattens a view of ranges into a view |

split_view/split |

It takes a view and a delimiter and splits the view into subranges on the delimiter. The delimiter can be a single element or a view of elements. |

counted |

A counted view presents a view of the elements of the counted range ([iterator.requirements.general]) i+[0, n) for an iterator i and non-negative integer n. |

common_view/common |

takes a view which has different types for its iterator and sentinel and turns it into a view of the same elements with an iterator and sentinel of the same type. It is useful for calling legacy algorithms that expect a range’s iterator and sentinel types to be the same. |

reverse_view/reverse |

It takes a bidirectional view and produces another view that iterates the same elements in reverse order. |

elements_view/elements |

It takes a view of tuple-like values and a size_t, and produces a view with a value-type of the Nth element of the adapted view’s value-type. |

keys_view/keys |

Takes a view of tuple-like values (e.g. std::tuple or std::pair), and produces a view with a value-type of the first element of the adapted view’s value-type. It’s an alias for elements_view<views::all_t<R>, 0>. |

values_view/values |

Takes a view of tuple-like values (e.g. std::tuple or std::pair), and produces a view with a value-type of the second element of the adapted view’s value-type. It’s an alias for elements_view<views::all_t<R>, 1>. |

You can read their details in this section of the Standard: https://timsong-cpp.github.io/cppwp/n4861/range.factories

Plus as of C++23 we’ll get the following:

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

repeat_view/views::repeat |

a view consisting of a generated sequence by repeatedly producing the same value |

cartesian_product_view/views::cartesian_product |

a view consisting of tuples of results calculated by the n-ary cartesian product of the adapted views |

zip_view/views::zip |

a view consisting of tuples of references to corresponding elements of the adapted views |

zip_transform_view/views::zip_transform |

a view consisting of tuples of results of application of a transformation function to corresponding elements of the adapted views |

adjacent_view/views::adjacent |

a view consisting of tuples of references to adjacent elements of the adapted view |

adjacent_transform_view/views::adjacent_transform |

a view consisting of tuples of results of application of a transformation function to adjacent elements of the adapted view |

join_with_view/views::join_with |

a view consisting of the sequence obtained from flattening a view of ranges, with the delimiter in between elements |

slide_view/views::slide |

a view whose Mth element is a view over the Mth through (M + N - 1)th elements of another view |

ranges::chunk_view/views::chunk |

a range of views that are N-sized non-overlapping successive chunks of the elements of another view |

ranges::chunk_by_view/views::chunk_by |

splits the view into subranges between each pair of adjacent elements for which the given predicate returns false |

ranges::as_const_view/views::as_const |

converts a view into a constant_range |

ranges::as_rvalue_view/views::as_rvalue |

a view of a sequence that casts each element to an rvalue |

ranges::stride_view/views::stride |

a view consisting of elements of another view, advancing over N elements at a time |

See all at https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/ranges

Summary

In this blog post, I gave only the taste of C++20 Ranges (and even have a quick look at C++23).

As you can see, the idea is simple: wrap iterators into a single object - a Range and provide an additional layer of abstraction. Still, as with abstractions in general, we now get lots of new powerful techniques. The computation model is changed for algorithm composition. Rather than executing code in steps and creating temporary containers, we can build a view and execute it once.

Have you started using ranges? What’s your initial experience? Let us know in the comments below the article.

References

I've prepared a valuable bonus for you!

Learn all major features of recent C++ Standards on my Reference Cards!

Check it out here: